- Ireland’s Daily Drug Docket: Punish the Profiteers, Treat the Addicted.

- Hard on Supply, Human on Use: Time for Common Sense in Irish Drug Policy.

Spend any time around a District Court and you quickly get the sense of a system carrying a weight it was never designed to hold. Day after day, more people find themselves before the courts on drug-related charges; possession, small-scale supply, probation breaches linked to use, and the petty crimes that trail behind addiction, like a shadow.

The scale is not anecdotal. In 2023, the courts made 21,907 orders in relation to drug offences in the District Court alone, involving 15,858 defendants.

The wider crime picture is hardly reassuring either: the CSO recorded 16,119 incidents of controlled drug offences in 2024, and noted that the decline that year included falls in both possession for sale/supply and personal use incidents.

Even if the trend line moves up or down in a given year, the reality in communities is constant: drugs are an everyday presence, and the courts are one of the last public services left standing at the point of crisis.

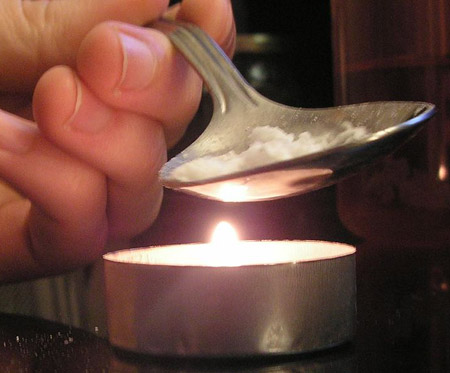

Against that backdrop, it infuriates decent people to see what looks like “soft” sentencing for dealers, especially when the damage is so visible. Families are burying loved ones. The Health Research Board recorded 343 drug poisoning deaths in 2022, a grim number behind which sit real kitchens, real bedrooms, real unanswered phones.

So why, people ask, does someone caught dealing sometimes receive a shorter sentence because they have no previous convictions and plead guilty early?

The first uncomfortable answer is that sentencing in Ireland is not a simple “one crime, one fixed penalty” system. Judges set a sentence based on the seriousness of the offence, then adjust it for aggravating and mitigating factors. Two of the most common mitigating factors are (a) no previous convictions, and (b) an early guilty plea.

The logic of the guilty plea is not mysterious, even if it sticks in the throat. A timely plea saves court time, shortens lists, avoids a contested trial, and often spares witnesses the ordeal of giving evidence.

Citizens Information says plainly that you can generally expect a reduced sentence for pleading guilty, because it saves time and can be seen as remorse.

The Director of Public Prosecutions’ own guidelines also recognise that a guilty plea is a factor to be taken into account in the mitigation of a sentence.

A clean record is treated as relevant because courts look not only backwards at wrongdoing, but forwards to the likelihood of rehabilitation and reoffending. It doesn’t mean “good character” cancels out harm. It means the system is trying, sometimes clumsily, to calibrate punishment to a person as well as to an act.

None of this means the law is blind to serious trafficking. Ireland’s Misuse of Drugs Act has a specific high-value supply offence, the well-known €13,000 threshold, aimed at commercial dealing and importing.

Citizens Information summarises the core idea: for importing drugs at that level, there is a very severe sentencing framework, with limited scope to depart where the court finds exceptional circumstances.

In other words, at the top end, the law’s intent is deterrence and long sentences.

If the public perception is that dealers “walk free”, the more likely explanation is that many of the cases clogging lower courts are not kingpins, but street-level, low-level, or messy hybrid cases where addiction and dealing overlap, and where the headline seriousness is assessed differently.

But the deeper question is not really about discounts for pleas. It is about who we choose to blame.

In the public conversation, users are often spoken about as if they are simply reckless, selfish adults who should carry full moral responsibility for every ripple of harm that follows. Yet, as anyone who has watched addiction up close knows, dependence is not a lifestyle accessory.

It is frequently bound up with trauma, mental ill-health, homelessness, coercion, and despair. That reality is precisely why the Citizens’ Assembly on Drugs Use recommended that the State introduce a comprehensive health-led response to possession of drugs for personal use, responding primarily as a public health issue rather than a criminal justice issue, even while possession remains illegal.

This matters because criminalising users can make the problem worse. A conviction narrows employment, housing, and education options. Shame drives people away from services. Fear keeps people silent when they should be calling for help. Meanwhile, organised supply adapts, recruits, and replaces. If we’re honest, the criminal courts are often being asked to do the work of health, housing and social care, at the wrong end of the pipeline.

That doesn’t mean turning a blind eye to crime. It means recognising different roles in the drug economy and responding accordingly. A person in addiction who possesses a small amount is not the same as the person profiting from others’ dependence. The law already distinguishes, but our rhetoric often doesn’t.

There are also practical models that point in a better direction. The Drug Treatment Court in Dublin is explicitly designed as a supervised treatment and rehabilitation programme for offenders with problem drug use, as an alternative to custody in suitable non-violent cases. It is not soft. It is structured. It requires engagement, monitoring, and consequences for non-compliance. But it is at least an admission of reality: that for some offenders, reducing harm and reoffending means treating addiction rather than simply warehousing it.

So where does that leave the public anger, the very real anger, at dealers and the devastation around them?

We should direct it with precision. The profiteers, the organisers, the coercers, the groomers of teenagers, the ones who intimidate communities and treat addiction as a business model, they deserve the full force of law and sustained policing pressure. The legislation exists to impose very serious sentences in the higher-end cases, and it should be applied firmly where the evidence supports it.

But if we keep pouring users through the courts as if punishment alone will cure dependency, we will continue to fill lists, fill cells, and fill graveyards, while congratulating ourselves on being “tough”.

A country can be hard on the trade and humane to the addicted at the same time. In fact, if we want fewer victims, it is the only approach that makes any sense.

Leave a Reply