Michael Hogan (1828 – 1899), was an Irish poet, known as the “Bard of Thomond”. He was born in Thomondgate, Co. Limerick to a father whose occupation was that of a wheelwright. Same father was also an accomplished musician, who made his own flutes and fiddles.

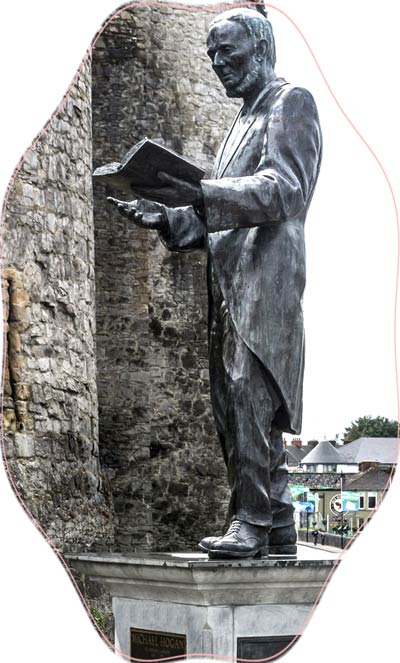

Indeed, a life-size bronze memorial statue, by sculptor Mr Jim Connolly, of Michael Hogan can be observed on your next visit to Limerick city; same erected back in 2005, at King John’s Castle, Plaza.

Indeed, a life-size bronze memorial statue, by sculptor Mr Jim Connolly, of Michael Hogan can be observed on your next visit to Limerick city; same erected back in 2005, at King John’s Castle, Plaza.

Hogan’s circulated work appeared in such publications of the period as:- the Anglo-Celt; the Irishman; the Nation; the Munster News, and the Limerick Leader.

His first volume of works, “Lays and Legends of Thomond“, was published in Limerick in 1861 and in Dublin in 1867. A further series of satirical publications, lampooning prominent city figures caused a great sensation at the time, enjoying a large circulation.

A new version of his “Lays and Legends” was published in Dublin in 1880 and six years later he undertook a visited to the United States, where he stayed for some three years.

Possibly best remembered for his epic long poem, ‘Drunken Thady and the Bishops Lady’, a little known poem entitled “The Battle of Thurles” is also attributed to Michael Hogan’s penmanship.

The Battle of Thurles – 1174.

King Henry II of England feared that the Normans intended to throw off their allegiance to him and set up an independent state in Ireland. One of those who took the oath of fealty to the British King Henry, was Dónal Mór O’Brien, king of Limerick or Thomond, a territory that embraced Co. Clare and the greater part of counties Tipperary and Limerick. Dónal Mór O’Brien leader of the warrior race of the Dalcassians soon learned that this submission to Henry afforded him little or no protection from incursions into his territory by the land-hungry invaders, and he was determined to resist.

Indeed the Norman invader Richard de Clare, 2nd Earl of Pembroke, (better known as ‘Strongbow’) decided to chastise him, and with his lieutenant, Hervé de Marisco, led a strong force from Waterford towards Co. Tipperary, plundering the countryside on the way, including the monastery of Lismore. He further summoned assistance form Dublin, and a well-armed force of Ostmen (persons of mixed Gaelic and Norse ancestry), led by experienced knights set out to join him. While awaiting their arrival, Strongbow encamped at Cashel. Dónal Mór O’Brien had intelligence of their approach and led his army from Limerick to meet them. A fierce engagement took place at Thurles in which the Normans were routed, suffering their first major defeat, while leaving four of their commanders and over 700 of their men dead on the fields of Laghtagalla, (Irish “Hollow of Blood”).

A now chastened Strongbow force fled in confusion to Waterford. Finding the news of the Thurles defeat had long preceded him, and the Waterford populace had risen up and killed the Constable of the town and some 200 of the garrison; he was forced to shut himself up, with the remnants of his forces, on the 420 acre ‘Little Island’, in the River Suir, on the eastern outskirts of Waterford City. He remained confined there for a month until Raymond FitzGerald le Gros (nicknamed Le Gros “the Fat”) arrived from Wales with about 450 men, to relieve him from a most perilous of situation.

The rank and file of the Normans attributed this defeat to sheer inept leadership. Their most experienced commander, Raymond le Gros, had previously withdrawn to Wales because of disputes with Strongbow. Raymond had demanded from Strongbow the Constableship of Leinster and the hand of his illegitimate daughter, Basilia (widow of Robert de Quincy), in marriage, but both requests had been refused. Strongbow now had to swallow his pride and send a messenger to beg Raymond to return, promising to accede to his requests. Raymond came over, landed at Wexford, then proceeded to Waterford and rescued Strongbow, whom he conveyed to Wexford where the marriage with Basilia was celebrated.

“The Battle of Thurles” by Michael Hogan, ‘Bard of Thomond’.

The war-fires light gleamed red all night, along the mountain gloom.

King Dónal’s men are up again, from Limerick to Slieve Bloom.

From glen and wood, the bone and blood of his fierce and fearless clan,

In wild array, at dawn of day, o’er Ormond’s plains swept on.From Waterford the Norman hoarde to the plains of Ikerrin came.

In vengeful haste the land to waste with sword and destroying flame.

Left and right with sweeping might, the headlong hosts engaged

And life ne’er bled, in a strife so red, while that combat of bloodhounds raged.But as the heave of the mad sea wave is barred by the crag filled shore,

So that iron tide, on Durlas’s side, was stopped by King Donald Mór.

There’s revelry high and boisterous joy from Cashel to Shannon’s shore,

And Luimneach waits to open the gates, for her conquering Donald Mór.

Archdeacon and historian Giraldus Cambrensis wrote at that time, that all Ireland was so heartened by the news of O’Brien’s victory that there was a general uprising against the invaders whose castles and strongholds were burned and destroyed, right up to the confines of Dublin. However this unity of purpose was short-lived. Disunion made its appearance again and soon the sad spectacle of petty Irish chiefs could be observed assisting the invaders against their Irish fellow-countrymen. The Normans took advantage of this disunity, and in the very next year 1175 Raymond Le Gros seized and occupied O’Brien’s town of Limerick, but again, in the following year, O’Brien expelled this garrison burning the town to the ground.

It is believed that in 1179, Raymond le Gros took possession of Thurles, while O’Brien was away ingloriously fighting his countrymen, the MacCarthy clan. If the town was fortified and garrisoned at this time, the Norman hold on it must have been exceedingly tenuous for shortly afterwards O’Brien and his entourage are found traversing this territory, without obstruction or impediment from these same foreigners.

Leave a Reply