Back in October 2018 it was reported that the remains of 796 children, buried in an unmarked mass grave at a former Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, Co. Galway, were to be exhumed as part of a major forensic investigation.

The story emerged from research undertaken by Irish amateur historian Mrs Catherine Corless. The latter had decided to write an article about this mother and baby institution, based on her own childhood memories of the said institution; having gained an interest in local history, through her attendance at evening history courses.

A slow news day saw national and international media take up the story, likening same to Rwandan genocide, Ireland’s own Holocaust and the Srebrenica massacre of the mid 1990’s. Leading members of our Irish Parliament, the Irish Senate and the Northern Ireland Parliament, latter despite supposedly being well educated, were unaware of Ireland’s past history and now all spent valuable hours in debate, many strongly condemning Roman Catholic church authorities regarding this issue.

But all of Irish society remained defined by its very silence and its total complicity in what was accomplished, in an effort to cover up what we must regarded today as the most shameful of chapters in our Irish history and a crime against Irish women and children.

Since then, the current Fine Gael Minister for Children, Ms Katherine Zappone has confirmed that it is the current governments intention to exhume and if possible, to identify remains. The Minister has further ratified the costs of this project at being between €6m and €13m. The Roman Catholic religious congregation of the Sisters of Bon Secours have offered “a voluntary contribution” of €2.5m.

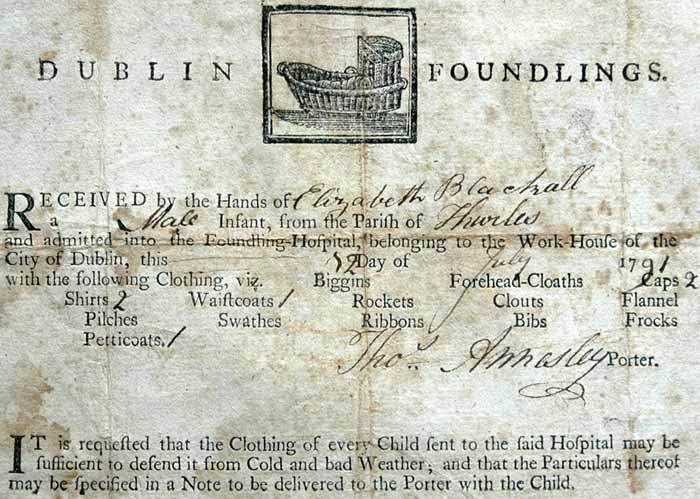

Thurles & Dublin Foundling’s Hospital

The Dublin Foundling’s Hospital (today the St. James’s Hospital campus and sometime in the future to become part of the new National Children’s Hospital at a cost in excess of €1.4bn) was first established in the early part of the 18th century (1702), with Dean Jonathan Swift and Arthur Guinness being amongst those who served on the Board of Governors. Its purpose was to prevent the deaths, brought about through neglect; malnourishment; climate exposure and murder, all caused due to severe poverty. The Dublin Foundling’s hospital also had one other aim; to educate and rear the children taken into charge, in the Reformed or Protestant Faith, and thereby to strengthen and promote the Protestant Interest in Ireland.

Foundling

A foundling refers to an infant child that has been abandoned by one or both parents at birth. Same is brought about usually due to the mother feeling unable to care for her infant, usually for reasons of poverty, or quite often due to pressures both from family and society in general, latter being unable to accept the existence of an infant born “outside the blanket” or outside of wedlock.

You will note from the picture show above of a billet (A billet in today’s language means a ‘ticket’ or a ‘receipt’ in French, but it originally meant a ‘short note’), that a male child “by the hands of Elizabeth Blackall” from the Church of Ireland parish of Thurles, was admitted to the Dublin Foundlings Hospital on July 12th 1791. The Porter’s name is shown as Thomas Annesley.

Note from the billet, shown above, certain of the clothing names no longer in use today.

Biggins – A bonnet tied behind the neck and made of wool or linen.

Clouts – Diapers or nappies.

Flannel – A square of fabric wrapped around a child over the diaper or a long undergarment.

Forehead Clothes – Strip of cloth tied across the forehead to behind the ears for added warmth.

Pilches – Layers of cloth tied around the diaper in an effort to prevent leakage.

Swathes – Strips of cloth, usually of wool, wrapped around an infant’s body for warmth and to put pressure on the navel. Parents will be aware of the term Swaddling.

A levy, of £5 per year, would have been imposed on the parish from which the child was sent.

A feature of most foundling hospitals was a turning-wheel type mechanism set in a wall near the building’s main entrance. This particular system was so designed as to encourage mothers to bring their unwanted children anonymously to the hospital building, rather than to abandon them on doorsteps or in other out-of-the-way areas.

The hospital’s turning wheel appliance allowed for a basket to be attached, into which an infant could be placed at any time, day or night. A bell was attached to attract the attention of the hospital porter then on duty. The porter would then rotate the wheel mechanism, thus bringing the infant into the building’s interior. Such porters were instructed to take in all infants left in the basket / cradle and not to have any direct conversation with the individuals who had lodged a child.

Child abandonment due to poverty and illegitimacy has always been a problem in the past, and viewed in private by governments as the unacceptable face of unnecessary expense on state coffers. In medieval times babies were often abandoned in church or monastery doorways, in the hope that the religious, of all denominations, would take on the task of providing sustenance. After all, did not Jesus Christ insist, in the Gospel according to St. Matthew (Chapter 19 – Verse 14), that Christians should – “Suffer little children, and forbid them not, to come unto me: for of such is the kingdom of heaven”.

Once an infant was taken in charge, it was assumed that a mother gave up all future control. Mothers whose circumstances changed and who tried to contact their child, risked having it ‘exchanged’. This was undertaken by transferring infants to a sister institution in Cork in exchange for any Cork infants, who were also considered by authorities to be in similar danger of being re-contaminated by Papist parents.

Death Rates

In the year 1752, of the 691 children taken in charge by the Dublin Foundling’s Hospital, 365 children were dead by the end of that particular year. In 1757, burial of these children was described as being chucked, naked into a hole, some eight or ten infants at a time.

A report ordered by the Irish House of Commons regarding child mortality over the previous twelve years, ending in June 1796; same would reveal that of the 25,000 admitted more than 17,000 had died. Worse facts would be revealed in the five-year period between 1791 to 1796. Here, of the 5,016 infants sent to the Dublin Foundling’s Hospital infirmary, only one solitary child had survived.

The Select Committee to inquire into the Irish Miscellaneous estimates, published in 1829, recommended that no further financial assistance should now be given to the hospital. It stated the Dublin Foundling’s Hospital had not preserved life or and had failed to educate those placed in their care. Overall it found that the mortality rate amongst the foundlings were almost 4 death to every 5 infants taken in charge, while the total expenditure to the state was £10,000 per year. It was eventually shut down in 1838, by Charles Grant, 1st Baron Glenelg (Lord Glenelg then Irish Secretary) to be later used to accommodate South Co. Dublin Union Workhouse inmates.

The Modern-Day Solution to Ireland’s Unwanted Children

In our modern-day Ireland; supported by numerous politicians, currently both in government and in opposition, we have now found a new solution to this age-old problem. With effect from May 25th 2018, the Irish people to everyone’s shame, voted by 66.4% to 33.6%, to kill all unwanted infants, but this time while still in the womb.

Today, such wilful murder must be seen as an abuse of children once again funded by the Irish state, without the full consent of Irish taxpayers.

Leave a Reply