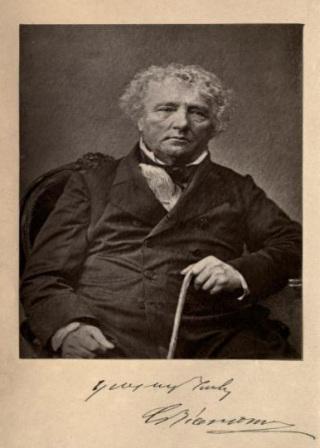

Thurles native, and always a welcome contributor to Thurles.Info, Mr Proinsias Barrett reflects romantically on Thurles, Tipperary, a changing Irish landscape and the life & times of Carlo (Charles) Bianconi (1786 – 1875).

Proinsias writes; “The Thurles connection with Charles Bianconi is interesting because I was aware that a late 19th century ancestor of Brodericks ‘of The Ragg,’ also provided a service similar, albeit on a smaller scale, to Bianconi. We were often told growing up that Martin Broderick, whose father Patrick moved from the Horse & Jockey area of Tipperary circa 1850, had business dealings with Charles Bianconi and went on to develop a respectable hackney service himself. Family business dealings with Bianconi may have been in the form of taking over some routes once used by the Bianconi operation and the development of contacts along these various routes, where teams of horses could be changed and collected on long haul trips. In fact Martin Broderick often went from Thurles as far as Galway with customers.

This tradition of horses and stables continues to this day with Martin’s Grandson Austin Broderick and Austin’s son Gregory and sister Cheryl, both developing horses not for drawing carriages but for prize racing and show-jumping at Ballapatrick Stables.

But Martin Broderick of the Ragg was an exception at the time and I have often wondered why Irish men had not already established hackney services throughout Tipperary before Bianconi. If we look at the times then and the predisposition of the majority of Irish people we might find some answer to that question.

As the story reads Bianconi arrived in Ireland in 1802, hardly four years after the 1798 Rebellion and the terrible counter insurgency measures conducted throughout Tipperary by the then ‘High Sherrif,’ one Thomas Judkin Fitzgerald (Fitzgerald being a surname he took in order to lay claim to a will, his real name was Tomas Judkin Unicke.). Known as ‘The Flogger Fitzgerald,’ he conducted his free-hand ‘interrogations,’ without bias towards sex or age, assisted by local Landlords and Yeomanry commanders like the Carden’s or Otway’s or Armstrong’s.

Robert Emmet the Dublin Barrister had also attempted rebellion in 1801. Penal Law, which had largely been relaxed during the 1760’s was once again enforced. Catholics, or native Irish for example, could not own land, own a horse worth more than £5, or have any formal education in Ireland. Without these how could one access credit or show collateral. Bianconi in 1801 had entered a country where 90% of the population had few or no rights. Some Catholics did succeed in business, being fortunate enough to have received an education in France, but the general atmosphere of business and politics in Ireland at that time favoured those of the ascendancy class.

I wonder if the same laws would have applied to Carlo Bianconi, being Italian we must presume that he was a Roman Catholic.

Religion and politics aside, I recently came across some interesting descriptions of conditions in Ireland for the weary traveller during the 18th & 19th century, pertaining in particular to the weather and the roads.

A German called Henrich Boll who travelled Ireland during the early 19th century noted that ‘the rain here is absolute, magnificent and frightening, to call this rain bad weather is as inappropriate as to call scorching sunshine fine weather.‘ Two centuries earlier an English Soldier called Fynes Moryson wrote after a night watch before the battle of Kinsale: ‘It groweth now about 4 o’clock in the morning as colde as stone and as darke as pitche, and I pray, sir, whether this is a life that I much delight in.’

Another called Thomas Stafford wrote of the wind coming off the snow covered mountains of Munster which ‘tested the strong bodies, whereby many turned sick, and some unable to endure the extremity, died standing sentinel.’

The English traveller Twiss wrote in 1755 ‘the climate of Ireland is more moist than that of any other part of Europe, it generally rains for four or five days in the week for a few hours at a time; one can see a marvellous rainbow almost daily.’

From ancient times a system of roadways around Ireland later used by Normans and Elizabethans contained many important landmarks and areas of archaeological antiquity, most nowadays are forgotten or replaced or by-passed. The late 18th early 19th century Scottish traveller, Lithgow, described the discomfort of travelling in Ireland using these ‘toghers,’ or causeways, particularly during winter when every day his horse constantly sank to its girths in the boggy road, complaining that his saddle bags were destroyed. He often had to cross streams by swimming his horses; during a period of five months six of them died or were drowned. In the end he felt as worn out as any of his steeds.

Finally Peter Sommervill-Large who in 1973 took the walk from Bantry Bay in Cork to Leitrim in wintertime retracing the lamentable steps of Donal Cam O’Sullivan Beare, Lord of Beare and Bantry, who in December 1602 marched the 300 or so miles to the territory of the O’Rourke’s in Leitrim with a thousand followers, arriving 15 days later with just 35 followers remaining.

Sommervill-Large describes the countryside he passes through on the walk in 1973 with admirable endearment and his subsequent book was very well researched. After crossing the Shannon at Portumna, through Eyrecourt, Aughrim and Ballygar in the direction of Glinsk, he mentions something I found interesting; ‘[The landscape] soon changed into numerous little hills and hollows with farms tucked into their sides, linked by a system of un-tarred country lanes.’

When I took one at random, I found that walking through the mud and the long narrow puddles in the deep ruts was an unexpected pleasure. The old dirt road has an intimacy, an ageless sense of belonging to the scene, and nothing changes the whole tenor of rural life more quickly than a coating of tarmac.

All the wild places are coveted now and are becoming trimmed and neatened, and the smell of petrol and diesel drifts over the country; there are few roads left like those Synge used to walk along. It seems unnecessary to tie down every remote section of the countryside with these bands of iron. I suppose one day when about five or six un-tarred roads are left, they will be preserved as national monuments.”

Leave a Reply